Posted November 07, 2025

By Byron King

The Lakes of Storm and Steel

Recently, I traveled to northern Minnesota, specifically to the legendary Iron Range, located north of Duluth. It was mid-fall; the sky was clear, the leaves were turning, and every view was beautiful, if not spectacular.

Good morning from northern Minnesota. BWK photo.

Good morning from northern Minnesota. BWK photo.

However, my purpose up north was not late-season tourism. I went there to inspect a promising mineral exploration project and learned a great deal. In due course, I’ll discuss investments, but not this particular one in Minnesota, as it’s still in its early stages. I have other ideas for you, of course.

First, I want to mention a few points of both history and money that popped into my scope as I traversed the Duluth Complex and drove around the upstate region. And in the next few sections, I’ll discuss some history, particularly as it pertains to mining. Also, I’ll say a few things about America’s steel industry, glaciers, the Great Lakes, and the upcoming anniversary of the total loss of a ship called the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank 50 years ago on November 10, 1975. All that and, in a broader sense, as you’ll see near the end, I want to lay out some thoughts on investment risk.

The Ore-Boats that Made America

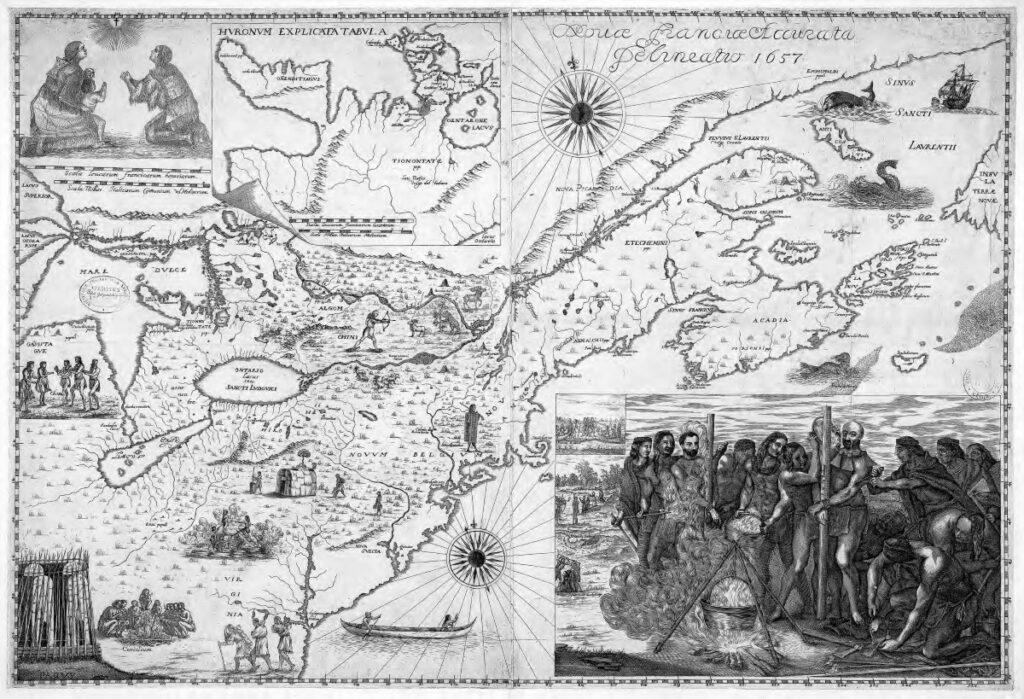

Let’s begin with a quick look back into the 1600s, when French explorers moved inland into North America. They used what was available and made their way mainly via large canoes on the Great Lakes.

From Montreal, the French paddled up the St. Lawrence River, across Lake Ontario, then via Lake Erie over to the passage north through what’s now the Detroit-Windsor region. Then they moved north into Lake Huron and perhaps made a sharp turn south into Lake Michigan; or in some instances, they went west across Lake Superior to what’s now Duluth. Indeed, many French city names along the way reveal the early history.

“An Accurate Depiction of New France,” 1657, Francesco Giuseppe Bressani. Library of Congress.

“An Accurate Depiction of New France,” 1657, Francesco Giuseppe Bressani. Library of Congress.

Those hardy explorers hauled trade goods inland to exchange with First Nations people for beaver pelts. It’s quite a tale, long-ago chronicled by historians like Francis Parkman. But for reasons of time, I’ll skip ahead by a few hundred years, except to say that the first Europeans found near-endless expanses of high-quality timber along the way, plus occasional outcrops of mineral deposits.

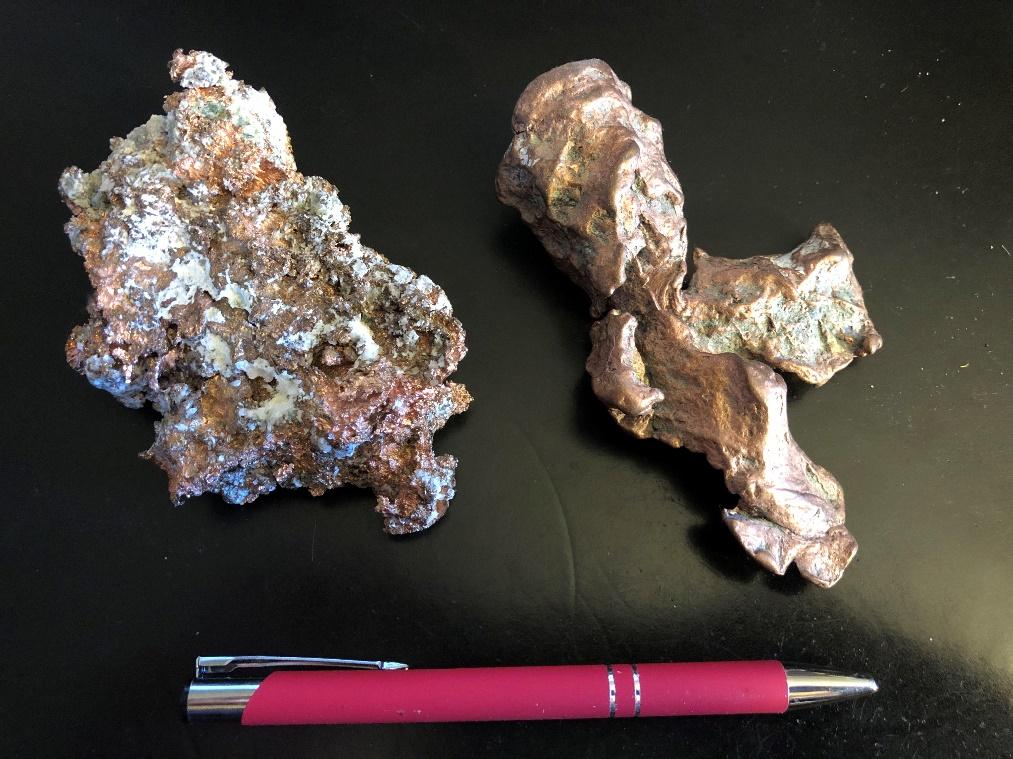

Now, fast-forward to the early 1840s, when native, elemental copper was discovered on the Keweenaw Peninsula of northern Michigan. This led to America’s first westward mining rush, predating California’s Gold Rush by about eight years.

Elemental copper from Keweenaw, Upper Peninsula of Michigan. From the BWK collection.

Elemental copper from Keweenaw, Upper Peninsula of Michigan. From the BWK collection.

For reasons dating back over two billion years, a large stretch of mid-continent bedrock is enriched in copper, as well as other elements such as nickel, iron, platinum, palladium, and others. It’s a treasure chest, and in the Keweenaw region, copper is exposed literally at the surface. Indeed, during the Pleistocene Era, glaciers plowed up the ground and redeposited chunks of copper across the landscape.

The Michigan copper boom of the 1840s created the need for sturdy, industrial-scale ships to transport metal south from the upper Great Lakes region. Among other destinations, Michigan copper went by barge across the Lake waters, and then through various canals to Pittsburgh, located in an area rich in coal deposits (aka “energy”). And thus began that city’s long association with smelting metals.

Now, move to the 1870s when prospectors and geologists uncovered swaths of what’s called “banded iron” in northern Minnesota, also a geologic legacy of Precambrian time. Another mining boom resulted from this discovery.

Jasper and iron in banded iron formation, Soudan, Minnesota. Courtesy Geologyin.com

Jasper and iron in banded iron formation, Soudan, Minnesota. Courtesy Geologyin.com

This time, a key player was John D. Rockefeller, of Standard Oil fame. That is, in addition to consolidating America’s oil business in the late 1800s, Rockefeller also went into the iron ore business. He invested heavily in a string of mines in the Duluth Complex, as well as a fleet of industrial-scale vessels to haul ore south to steel mills in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and even New York.

From the 1870s to now, Great Lakes ore-boats have hauled their cargo from Minnesota and the Iron Range. They loaded up at docks along Lake Superior and sailed to mills down and across the Midwest. At first, it was banded iron ore. However, when those deposits began to deplete, the mining firms developed another type of iron ore called taconite. (Long story; not here.)

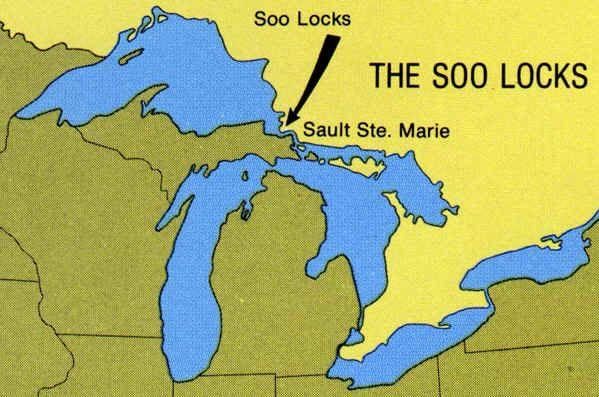

Whatever the ore-boats haul, whether banded iron or taconite, their design must be relatively long and narrow, “skinny,” one can say. In fact, the hull shapes of ore-carriers are dictated by the length and width of a series of narrow locks around Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, known as the “Soo Locks.”

Soo Lock system, Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

Soo Lock system, Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

Year after year, decade after decade, generation after generation, Great Lakes ore-carriers have moved steadily and predictably, considering that the lakes are ice-bound in winter. For about nine months of every year, they make their runs, hauling iron ore across Lake Superior to unloading facilities. Destinations along Lake Michigan include the Chicago area and Gary, Indiana. Or the ore went to sites in the east, such as Detroit, or further along the Lake Erie shoreline of northern Ohio and Pennsylvania, from Toledo to Cleveland, Erie, and as far as Buffalo.

American industry has long made good use of Minnesota’s iron ore. For example, over many decades at Henry Ford’s integrated complex at Rouge River, south of Detroit, iron ore entered one end from straight off the boat and emerged at the other end of the plant as a Ford automobile.

Indeed, America’s industrial Midwest could never have become what it was, nor could America have become the powerful nation that it is, without Minnesota iron and those fleets of ships that hauled it from the mines to the mills. And as you can imagine, there was money to be made by transporting ore, which brings us to a famous maritime name and its tragic demise fifty years ago.

“The Ship Was the Pride of the American Side”

Let’s begin by noting that a Great Lakes ore-carrier has one task; namely, to haul its cargo from Minnesota to unloading facilities in the south. The routes are predictable: down and back, perhaps three times every two weeks, up to 50 times per year as long as there’s no ice. So, everything about constructing ore-ships and their operation is focused on low costs, but also heavily biased toward reliability and efficient sailing. Sunken ships and lost loads make money for no one.

Meanwhile, cash flow from owning and operating an ore-carrier has long been predictable. In fact, at one point in the 1950s, the Northwest Mutual Insurance Company decided to construct a vessel to buttress its portfolio of long-term investments that back up its policies.

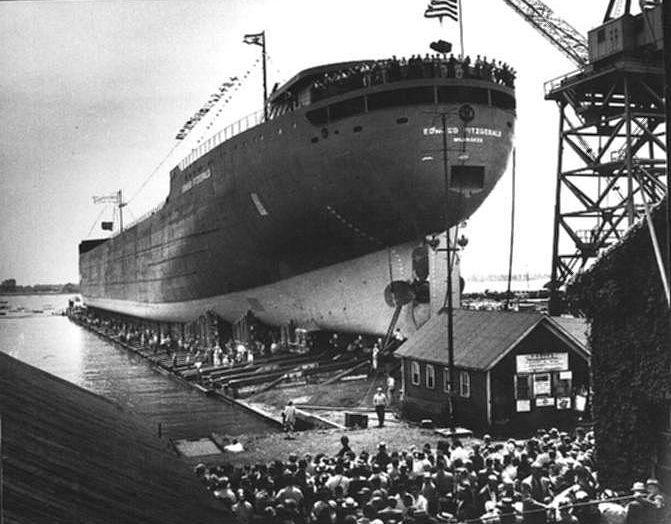

SS Edmund Fitzgerald, launched June 8, 1958. Courtesy Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

SS Edmund Fitzgerald, launched June 8, 1958. Courtesy Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

And thus, in 1958 came a well-built vessel called the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, named after the then-CEO of the Milwaukee-based insurance company. (For the sake of accuracy, Mr. Fitzgerald did not want a ship named after him; it was a decision by the board.)

SS Edmund Fitzgerald. Courtesy Jobbiecrew.com.

SS Edmund Fitzgerald. Courtesy Jobbiecrew.com.

The “Fitz,” as she was called, was quite a vessel both as ore-carriers go and in other respects. She was built in a shipyard near Detroit, using the highest grades of naval steel. She had the latest features in design, including advanced marine propulsion, navigation, and excellent crew accommodations. All that, and even two luxurious VIP suites to rent out to paying customers who wanted a sailing voyage that revealed certain industrial mysteries of a Great Lakes passage, including sailing through the Soo Locks. (And indeed, those suites were constantly rented by adventurous passengers.)

From the late 1950s to November 1975, the Fitz was sturdy and reliable. She plied her routes under a series of captains and always attracted top-notch crew. But then, one night, the dark forces of nature and fate caught up with this ship, an angry duo of Aeolus and Poseidon, to use classical references.

The Gales of November

Geologically, the Great Lakes are glacial and post-glacial features. That is, they are massive depressions – lake “basins,” to use a geological term – carved by glaciers. In essence, the five Great Lakes follow pre-existing zones of weakness within the underlying bedrock and crust, areas where glaciers scooped out really big holes, so to speak.

Plus, the Great Lakes are considered mostly “fossil water” in the sense that almost all of it dates back to glacial and immediately post-glacial time. In other words, the Great Lakes are not mere depressions in the ground filled up by rainfall, snowmelt, and stream runoff. They are relics of the Ice Age.

Meanwhile, the Great Lakes are among the largest inland bodies of water on the face of the planet. Together, they constitute about 20% of the world’s freshwater. Millions of people rely on the Great Lakes for drinking water, and the region supports a large economy due to the water's use in industry, agriculture, and recreation.

Geographically, large areas of every lake – certainly, the vast surface of Lake Superior – are such that there’s no seeing the shoreline due to the curvature of the earth, and this alone contributes to unique forms of weather. Plus, the freshwater of the Lakes creates a surface that you won’t find in saltwater seas; that is, there’s a density difference between salt and freshwater, and related differences in surface tension that create entirely different wave shapes in the Great Lakes.

Now, add early winter weather, namely Arctic winds that blow down in late fall across Western Canada towards the Great Lakes region. These create what are called “the gales of November.”

That is, extremely cold, Arctic air blows across relatively warm Lake Superior water; although to be sure, Lake Superior is always cold and nearly unswimmable by mere mortals, at least not without a wetsuit or drysuit. This air-water phenomenon creates humidity that leads to rapid ice formation on any object that protrudes into or near the water, such as a ship. In other words, your vessel can rapidly become encased in ice.

And back to those freshwater waveforms that build up beneath the blowing cold winds. In terms of hydrodynamics, it’s more than possible to experience wave periods such that the bow and stern lift up quite far, relative to the midsection of the ship, leading the long, skinny vessel to sag amidships. Or the waves can elevate the midsection, causing the bow and stern to bend downwards, causing the ship to “hog.” One way or another, the hull of an ore-carrying vessel must be strong enough to absorb these stresses and not split in half.

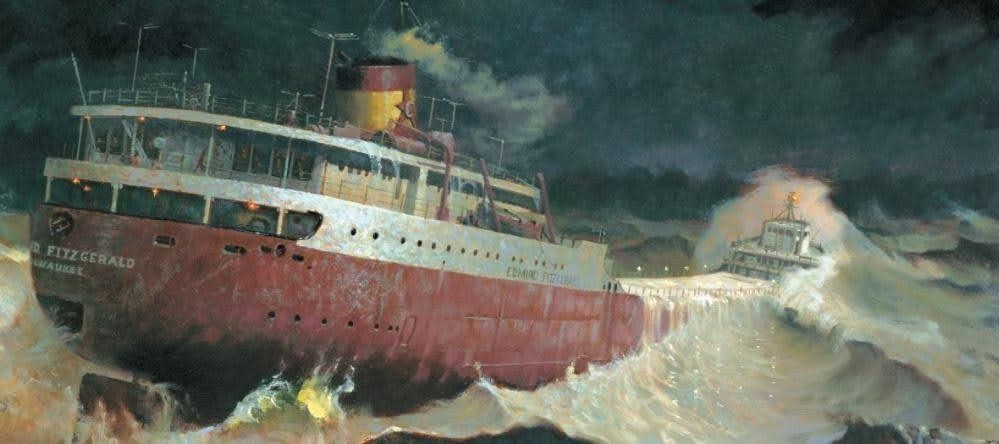

SS Edmund Fitzgerald on her last voyage. Courtesy Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

SS Edmund Fitzgerald on her last voyage. Courtesy Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

To make a long and tragic story short, on the night of November 10, 1975, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was caught in a massive, early-winter storm. She iced up and was bent and twisted by historically powerful waves. She split in half and sank in about 500 feet of water in eastern Lake Superior, with the loss of all 29 crew.

No one survived to tell the story, but here’s one version of the ship’s last moments from the lyrics of a well-known song by the late Gordon Lightfoot:

The captain wired in he had water comin' in

And the good ship and crew was in peril.

And later that night when his lights went out of sight

Came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Scale model of SS Edmund Fitzgerald. Courtesy Wisconsin Maritime Museum.

Scale model of SS Edmund Fitzgerald. Courtesy Wisconsin Maritime Museum.

Based on surveys of the wreckage, today the remains of the vessel’s front half rest upright, deep in the cold waters of Lake Superior. The stern lies inverted, some distance behind.

If you’re old enough, you might recall the story and the nationwide shock and sense of loss when the ship went down. If the story predates you… Well, it’s a deeply moving tale if such things move you.

If you want to know more, I highly recommend a recently published book by John Bacon, entitled The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald. The writing is superb, and Bacon gives a fascinating account of the ship, her crew, and the history of shipping on the Great Lakes.

Hedging Against Risk

Let’s end with some investment angles in all of this. Because, clearly, those ore carriers made a lot of money for many people for a very long time.

Indeed, no less than John D. Rockefeller made money by mining iron ore, and then his company, along with others, made money hauling the ore down to steel mills. Of course, the steelmakers also made a profit, enough to cover the freight costs of those fleets of ore-carrying vessels.

Year after year, it all seemed so steady, reliable, safe, and predictable. And indeed, the ore-carrier business was so predictable and financially sturdy that no less than Northwest Mutual Life Insurance bought a ship to serve as a low-risk cash cow.

But then came those Gales of November upon a ship owned by a life insurance company, no less… Which ought to give us all pause, because what really makes for a “safe” investment? Something can be safe, right up until the moment that it isn’t.

In other words, you should always ask yourself what risks are out there. What’s hidden or even what’s perhaps hiding in plain sight, if not just over the horizon?

This segues nicely with the long-term emphasis on owning precious metals, which we’ve hammered hard here in Strategic Intelligence. Own gold and take possession. It’s nobody else’s liability, not if you control it.

On the mining side, we have numerous excellent ideas. And to name just one, I’ve long been a fan of Contango Ore (CTGO), with mining operations in Alaska, as well as upside from exploration and redevelopment at other sites.

That is, Contango offers the solid cash flow of a working gold mine, located about midway between Anchorage and Fairbanks. The company partners with a solid major, Kinross Gold (KGC). Plus, there’s redevelopment potential for gold at the past-producing Lucky Shot Mine, just north of Anchorage. And there’s discovery upside too, with the company’s work at the Johnson Tract, about 130 miles southwest of Anchorage.

Remember: when buying shares, be sure to watch the chart, wait for down days, always use limit orders, and never chase momentum.

Owning precious metals and shares in solid mining companies are ways to hedge market risks. Although Wall Street is euphoric at the moment with a historic bull market, history has shown that things can change in an instant… as the crew of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald sadly discovered.

That’s all for now. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

The Start of the Metals Rebound?

Posted November 06, 2025

By Sean Ring

Cheney’s Legacy Is All Around You

Posted November 05, 2025

By Sean Ring

The Socialist Sandbox

Posted November 04, 2025

By Sean Ring

The Joyless Bull

Posted November 03, 2025

By Sean Ring

Go Big. Go Homer.

Posted October 31, 2025

By Sean Ring