Posted August 29, 2025

By Byron King

A Money Pit That Saved Investors?

Before I hand over today’s Rude to Byron, I’ve got some housekeeping.

First, since Monday is Labor Day, Paradigm’s offices are closed. I won’t be able to provide you with the Monthly Asset Class Report until Tuesday. However, that’s okay; you’ll still receive it before the market opens after the long weekend.

Second, a note on the unofficial Rude portfolio: I will place an order today to sell half of my SBSW holding and use the proceeds to buy VZLA (Vizsla Silver Corp). As my trustee must approve this trade before I sell it, you can front-run me and sell first (if you’re going to sell). Vizsla is a highly rated silver miner I’ve had my eye on for a long time. I’m up 75% on SBSW, and it looks like the uptrend is over for now. However, I want to continue holding a smaller position in anticipation of a recovery.

Third, enjoy this fascinating piece from Byron and have a wonderful, long, restful weekend!

Let’s discuss how gold has a history of saving investors during times of tumult, inflation, panic, recession, and even depression.

The tale I’m about to relate took place during the Great Depression, from 1929 through the 1930s, a period when many financial stories ended in hardship and sorrow. But not this one.

The action took place in the town of Lead (pronounced “Leed”), in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where there was (and still is) a money pit, but not in a negative sense like the term is used most of the time.

Homestake Mine’s massive old “Open Pit.” Courtesy AmericanBusinessHistory.com.

Homestake Mine’s massive old “Open Pit.” Courtesy AmericanBusinessHistory.com.

The South Dakota Money Pit

It’s all about a gold mine and a company called Homestake Mining, located in the Black Hills of South Dakota, in the southwest part of the state near Rapid City. Original prospecting in the region dates back to the late 1860s and early 1870s, immediately following the Civil War. The mine itself began its long life in 1876. But that initial search for yellow metal makes some of its own history.

Indeed, the quest for gold in the Black Hills had much to do with the presence of the U.S. Army, which was stationed in the plains to enforce the federal government's authority. And in June 1876, Colonel George Custer and his 7th Cavalry Troop met their fate at Little Bighorn, in nearby Montana. (Interesting tale; not here.)

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Courtesy U.S. National Park Service.

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Courtesy U.S. National Park Service.

Custer may have lost his scalp, but more than a few others made seriously good money out of the gold from the Homestake mine. In its day, this vast series of cuts and tunnels was among the world's largest and most productive holes in the ground. The ore was what we call “nuggety,” but wow, it was there in quantity.

Nuggety gold ore from Homestake Mine, South Dakota. BWK photo.

Nuggety gold ore from Homestake Mine, South Dakota. BWK photo.

Indeed, for about 125 years, generations of miners have dug out high-grade gold ore from the rocks beneath Lead. For our purposes today, let’s focus on the 1920s-30s, as it’s accurate to use Homestake as a proxy for the entire gold-mining industry during that era.

Generally, the U.S. experienced a period of prosperity during the 1920s. It was the so-called “Roaring Twenties,” a period during which the economy boomed and technology advanced (e.g., automobiles, petroleum, radio, and many more). And all was moving right along until the stock market crashed in October 1929.

Not all stocks crashed, however, as Homestake’s share price rose between 1929 and 1935, accompanied by a significant increase in both earnings and the dividend payout. In fact, Homestake's earnings per share (EPS) increased from $4.16 in 1929 to $32.43 in 1935. In other words, the gold miner showed annual compound EPS growth of 41%!

It’s also worth noting that much of this rise in Homestake’s share price occurred in 1930, 1931, and 1932, before Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) became president and seized the nation's gold in May 1933.

But even FDR's summary seizure of the nation’s gold didn't stop the upswing for Homestake. The stock, its earnings, and the handsome dividend continued to appreciate. It held firm through most of the early years of the New Deal, weathering all manner of harebrained, failed economic experiments that emanated from FDR and his so-called “brain trust” in Washington, D.C.

Looking back at the 1930s, much of the U.S. business economy suffered from declining earnings. From fields and farms to mines, mills, factories, shipyards, and businesses up and down every Main Street in the country, the economy more or less seized up. And this economic stagnation lasted until about 1939, when pre-war military spending began to ripple across the landscape.

At times during the Great Depression, national-scale unemployment rates reached over 25%. But through it all, the American gold mining industry was a hot spot of economic vibrancy, as illustrated by Homestake’s wealth protection and dividend payouts.

An Era When Half of the Banks Failed

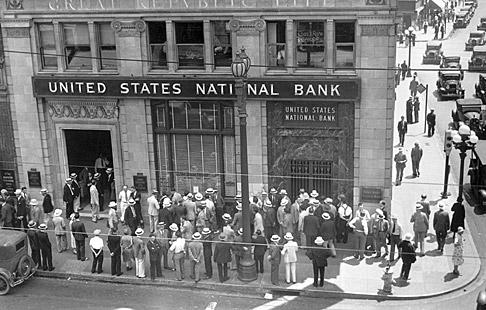

While we're revisiting the history of gold during the Great Depression, let's also consider what was going on with banks in the U.S.

According to economist John Walter, writing in 2005 in the Economic Quarterly of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, the U.S. went from over 31,000 banks in the mid-1920s to under 15,000 banks by 1934. That is, from the East Coast to the West Coast, over half of all American banks failed.

In 1933 alone, over 4,000 banks failed, which translates to about 80 banks per week, or 16 per business day. And back then, a bank failure was almost always a wipeout for depositors. There was no federal deposit insurance until late 1934, and even then, the initial coverage was a mere $2,500.

Bank run in Orange County, California, 1933. Courtesy Orange County Register.

Bank run in Orange County, California, 1933. Courtesy Orange County Register.

Most depositors in those 16,000 failed banks lost everything, with no recourse to their funds. If you were a depositor and didn’t pull out your cash in time, your savings went down with the ship.

Under the circumstances, times were tough for banks. They were marginally profitable, if they made any money at all. Interest rates on savings fell to the range of 1%, prompting one to wonder why people kept any money in banks, considering the high risk of failure and the possibility of sustaining massive losses. And when you understand this, it’s no wonder that many Depression-era people spent the rest of their days saving money in coffee cans in their basements.

The Homestake Payout

All the while, Homestake shareholders collected dividends in the range of 8-10%, plus capital appreciation. The Homestake dividend went from $7.00 in 1930 to an astonishing payout of $56 per share by 1935. For better or worse, hard times across the nation were somehow good for gold miners and mining companies like Homestake.

One explanation I've heard is that the after-effects of the 1929 stock market crash prompted the Federal Reserve to contract the money supply while reducing bank credit. In this sense, the Fed could not have been more wrongheaded, transforming what might have been a cyclical recession in 1929-30 into a decade-long depression.

With less credit across the economy, lending froze, and business lending dried up. According to historical accounts, many businesses, households, and individuals were simply unable to obtain credit, regardless of their circumstances. And economic growth just plain hit a wall.

History has made much of FDR’s New Deal programs, such as his "relief" payments, as well as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration. Yes, these sorts of transfers helped many individuals, but what the U.S. economy needed was basic capital investment.

The fact is that when most private capital investment ground to a halt during the New Deal, there was a dearth of fundamental capital formation in the economy. No matter how much FDR spent paying kids to build trails in national parks or paying artists to paint murals on post office walls, the economy couldn't get traction to move ahead.

Tight credit extended even to governments, and by extension to their fiat currencies. As world trade tightened due to protectionism, public credit also evaporated. Eventually, investors fled from paper currencies (even U.S. Treasuries). Big players in international finance converted paper currency into the only "money" that was not someone else's liability, and not subject to counterparty default, namely gold.

And how did things resolve? World War II undoubtedly changed the global dynamic. However, be cautious in how you view even this major event, because the war didn’t end America’s Great Depression; instead, the war ended FDR’s New Deal, which ultimately led to the end of the Great Depression.

Meanwhile, the takeaway for today is… Own Gold!

That’s all for now. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

X Marks the Stocks

Posted September 05, 2025

By Byron King

Google’s Great Escape

Posted September 04, 2025

By Sean Ring

Red China’s Silicon Kill Switch

Posted September 03, 2025

By Sean Ring

Silver Minings Playbook

Posted September 02, 2025

By Sean Ring

A Philosophy For Living

Posted August 28, 2025

By Sean Ring